Tātara e maru ana - the sacred rain cape of Waiapu Kōkā Hūhua

2017

Centuries ago, Tāmokai of the inland Te Aowera people spoke to his kinsman Kōkere and said: “Hoake tāua ki te Waiapu tātara e maru ana—Let us go to Waiapu, where the rain cape is thick.” This proverbial reference to a woven rain cape, usually made of harakeke (Phormium tenax), speaks of the shelter provided by the richly forested Waiapu valley, here on the East Coast of Aotearoa. The image of prosperity is reinforced at the end of the first verse of the Horouta Waka pātere composed by Arapeta Awatere: Kei Waiapu te tainga o te riu o Horouta, Ko te iwi tēnā Ngāti Porou, Tātara e maru ana which refers to the Waiapu where the emptying of the Horouta canoe took place, and to the beginnings of Ngāti Porou around the river, where they lived in great numbers. The Horouta waka is renowned for bringing kūmara to Waiapu, where this prized crop was extensively cultivated.

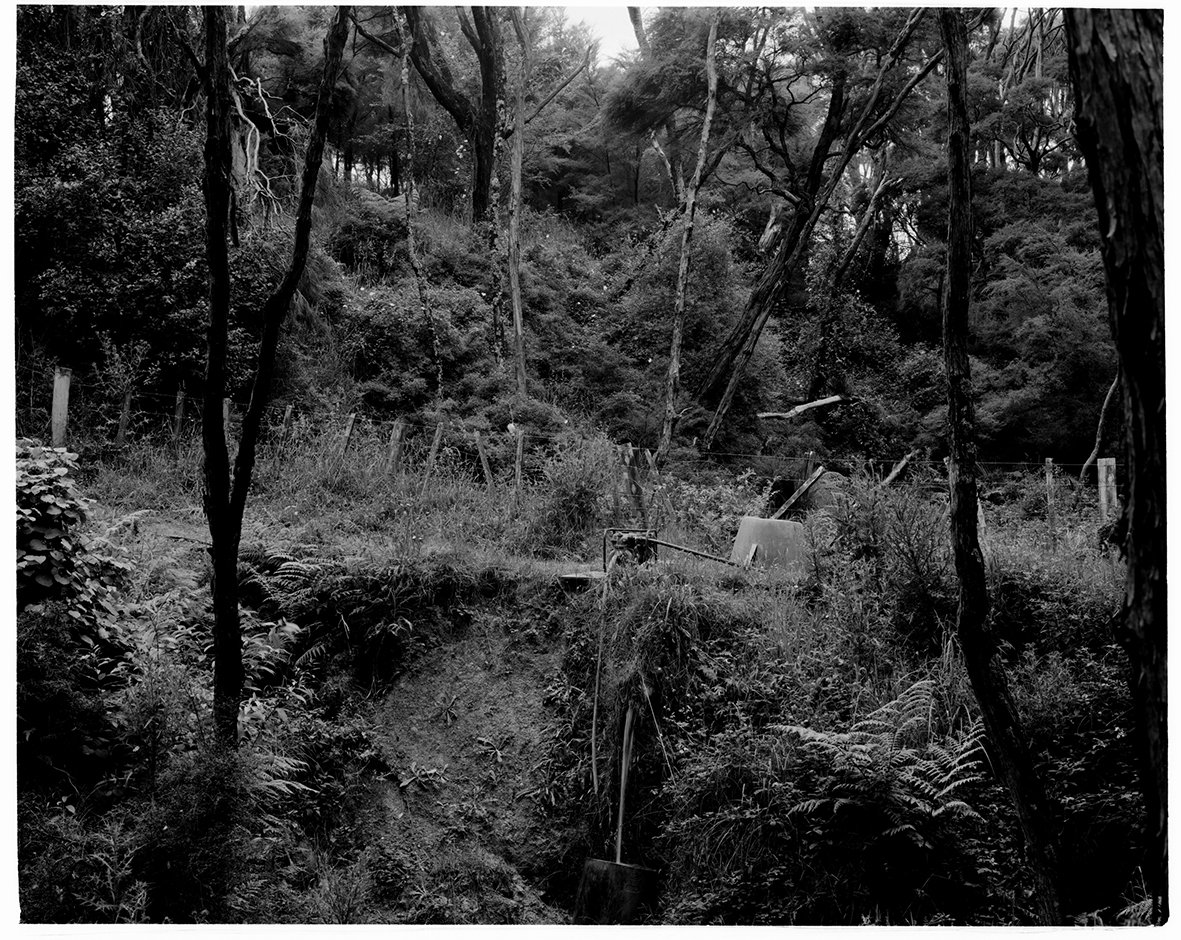

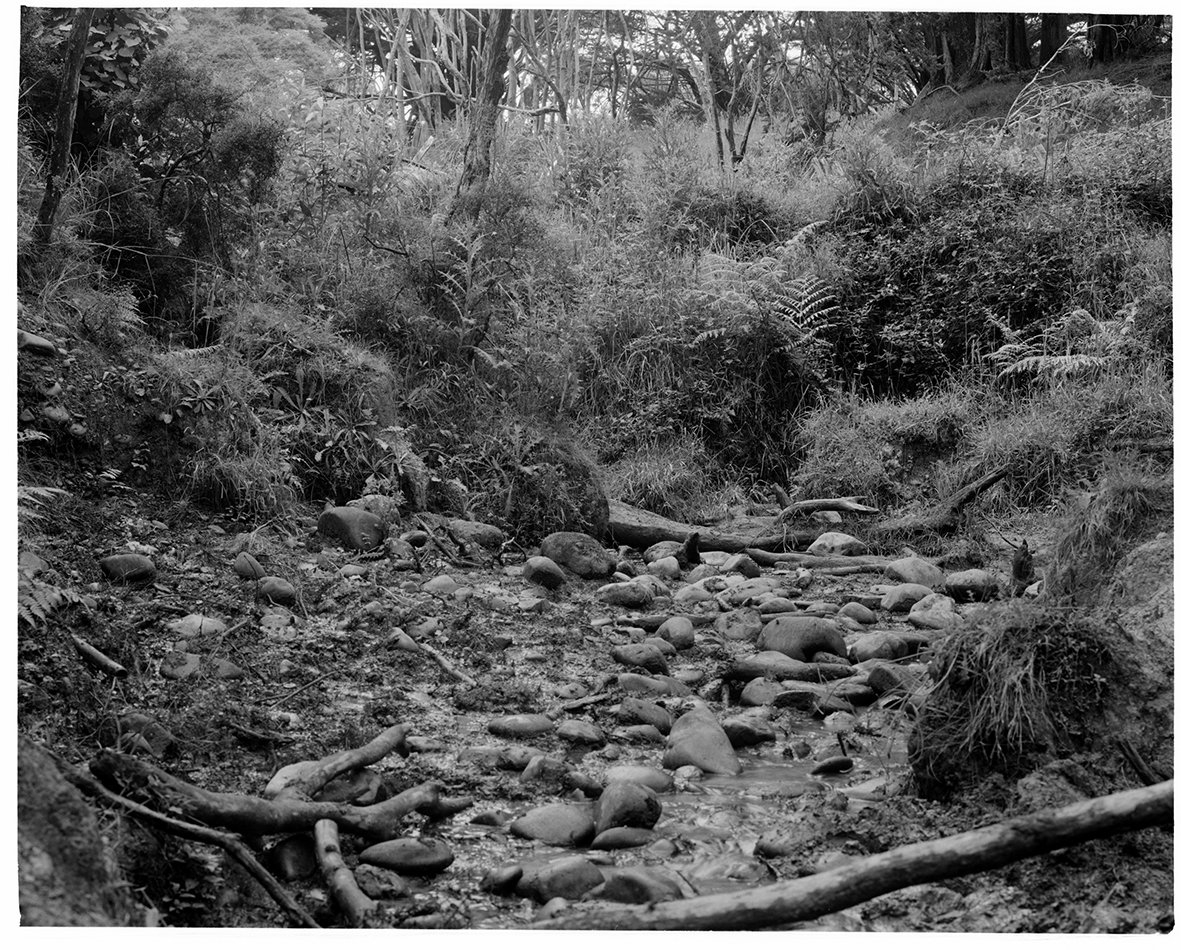

According to Tā Āpirana Ngata: “…the Waiapu river in its lower reaches made up for its steep, broken and sometimes violent course by the great extent of cultivable land on both banks backed by terraces suitable for pa sites. Hence the great development of the population there, which drew from Tāmokai of the inland Aowera tribe the cry, “Hoake taua ki Waiapu ki tatara e maru ana”. When the words were first uttered by Tāmokai, he imagined a sanctuary, a safe haven for rising generations. With abundant food cultivations, freshwater springs, ample material wealth, and a flourishing culture, Te Riu o Waiapu was indeed a haven. Today, the Waiapu River is in the midst of a century-long catastrophic environmental disaster due to deforestation. Waiapu Kōkā Hūhua is an ancestral mother of many; a river of many female leaders. In response to mass erosion, Te Runanganui o Ngāti Porou iwi and hapū have set forth a one hundred-year plan for the revitalization of the river called Waiapu Kōkā Hūhua in partnership with the Gisborne District Council and Ministry of Primary Industries. They agreed on a shared vision for the restoration of healthy land, rivers and people.

In the 2012 Waiapu River Catchment Study Final Report, hapū identified ‘desired state’ environmental indicators including that ‘Underground springs are used and protected’. Elders speak about times when there was ‘a tuna in every puna’, an eel in every spring to keep the water clean. Assisted by oral histories and land court records, I work with my Te Whanau-a-Pokai hapū around Tīkapa Marae to locate freshwater springs and other sites of significance and markers in the land, to visually record their current state. This series of photographs and video is a direct response to the Waiapu Kōkā Hūhua plan.

How do we find hope and optimism in the face of unimaginably large-scale disasters? The scale of the Waiapu River erosion disaster requires many generations of restorative work. Yet healing the tributaries and freshwater springs of the catchment is conceivable in shorter timeframes. Our elders who once used freshwater springs maintaining strict tikanga (protocols), retell stories that inspire me. It is imperative to find collective ways to activate change to uplift the mauri (lifeforce) of the water in their lifetimes. Investigating ancestral places associated with water is important because they reveal the cultural and ecological mātauranga-a-iwi (tribal knowledge) of our tīpuna (ancestors), within tribal organizational boundaries marked by genealogies. A measure of a return to this way of thinking, is that water is looked after.

Today, I photograph for past-present-future generations, beyond my own lifespan. My desire comes from a wellspring of aroha for whenua, awa and moana, for the people who are the hau kāenga living ‘at home’ and for those like me, who renew ancestral connections. As a Ngāti Porou person, I had to begin with myself, re-invigorating my relationship with land and river, by learning from the ground up and being in the flow of the water.